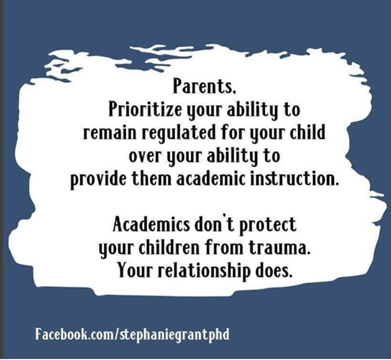

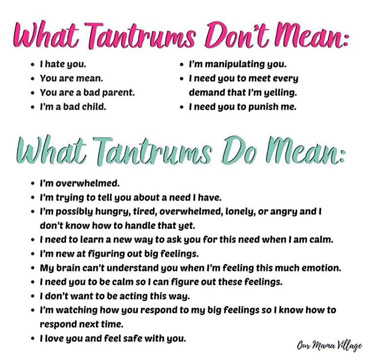

Recently, while browsing social media in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, I ran across the following two images: the first from the Facebook page of developmental psychologist Dr. Stephanie Grant and the second from the Instagram page @OurMamaVillage. These important statements inspired me to spend some time writing about this, as I realize some of these concepts are not self-explanatory to everyone out there.

At the therapy department of Child Advocates of Fort Bend, we use the terms “emotional regulation” and “dysregulation” a lot. These are key psychology concepts, especially in the context of treatment for trauma—which we specialize in.

So, here’s a definition to start:

“Emotional regulation refers to the process by which individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express their feelings.”

Self-regulation is important because it allows children and adults to do well in the various areas of their lives: school, work, interpersonal relationships, etc. It also very much impacts our self-image and self-esteem, and it makes us feel good about what we can handle in life. Or, on the contrary, if we feel like our emotions get “the best of us” on a consistent basis and we’re not able to regulate well, we may label ourselves in a negative way, leading to harmful feelings like shame.

The thing about emotional regulation is that children look to their caregivers to co-regulate.

Because of this, a child will not be able to develop better regulation skills than the ones they see in the environment in which they grow up. Children are NOT born with the ability to calm themselves down—i.e. think of toddlers who cry until they get their needs met: food, sleep, soothing. Young children resort to tantrums as a means of getting the caregivers’ attention because they still have not developed the language and awareness to communicate like we (adults) do. As children grow up, they will watch the adults around them to learn how to internally process feelings and outwardly react to situations, especially emotional crises.

So, if a caregiver tends to engage in behaviors like frequent screaming, hitting, throwing things, cursing, shaming, belittling, emotional numbness, etc. when they are in crisis, a child who witnesses this may (1) become afraid because the person who they look to for safety is not in control of their own emotions, (2) internalize feelings of shame if the behaviors are directed at them, i.e. “I am a bad child”, and (3) likely become even more dysregulated. Some children will shut down emotionally as a way to compensate for the high levels of emotion their caregiver is displaying. This child will appear “very calm,” but inside feel numb. This way of coping is called becoming “hypoaroused,” and it can be an issue later in life because the child may become so used to shutting down that they may have a hard time identifying and feeling their own feelings, both positive and negative ones. Being hypoaroused can also lead children and teenagers to disconnect from their bodies and “gut feelings” so that when they’re in risky situations later in life, protecting themselves may become harder. Then there’s the children who, when they experience a dysregulated caregiver, will become “hyperaroused.” This means that they will also scream, curse, and throw things— essentially matching or “one-upping” the behavior they’re seeing. If the caregiver perceives this as disrespect or as evidence that the child is not “listening” or complying with the caregiver’s disciplining, and becomes even more dysregulated, then child and caregiver enter a vicious cycle that really damages the relationship and erodes the child’s self-esteem. Both hypoarousal and hyperarousal in children can result in interpersonal issues later in life.

And listen, we’re human beings—not machines. It’s ok to “lose it” sometimes. There will be times when we’ll make mistakes and yell, be unfair to someone we care for or react in the heat of the moment. I’m not saying that losing control sometimes means being a bad parent or caregiver, or that it results in ruining a child’s life. Going back to apologize and correct when we make mistakes can repair the relationship and has the added benefit of modeling humbleness, self-awareness and genuine apologizing to children.

What I really want to leave you with, however, is that emotional regulation is very important and that it is NOT a matter of willpower only. Some people come from families where there was a high degree of dysregulation—likely as a result of generational trauma. If this is your case, and you’re telling yourself, “Next time I’ll control myself; I’ll just force myself to do better”—you may be in for a disappointment.

The good news is that emotional regulation is a skill, not an identity we’re either born with or not. When we didn’t know how to drive yet, we didn’t just tell ourselves, “I’ll force myself to drive and it will work.” We had someone else teach us and then we practiced what we learned. It’s ok to lack an emotional skill; that’s not our fault. But it is our responsibility to get the support we need to practice this skill—especially if it impacts others.

Therapy is a great place to start. Meditation and mindfulness are also really helpful in slowing us down. Have candid and vulnerable conversations with your children when things are calm and ask them how they perceive your reactions during high-emotion times and how it makes them feel. Take a free parenting class online if you think it may be helpful. Operate from a place where you are separating your child’s behaviors from who they are; your child did something bad, they are not bad. And if you’re so emotional that you can’t make that differentiation, take a break. Try not to discipline when you’re at your angriest.

Sometimes I hear parents say things like, “I just have a short fuse; it is who I am” or “a loud tone is just how I talk.” And while I see where they’re coming from, this sort of black-and-white thinking can be very limiting. A more constructive and hopeful thought could be: “I struggle to regulate emotionally. It’s a skill I did not have the opportunity to really develop early on in life, but I am committed to do the work and get better at it now so that it does not cause my children pain.”

It’s not too late. It can get better; YOU can get better at it—but there’s some work involved.

So, forget about that old phrase “do as I say, not as I do.” When it comes to emotional regulation, developing a healthy self-image and learning how to cope with challenges and strong emotions, children will do as we do, not as we say.

Elena Petre, LMSW

References:

- Gross and Thompson, (2007): Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations.